Art Historian Nikki Petroni shares some insights on Malta’s troubled evolution of modern art

It is generally held that modern art did not flourish, or developed particularly late in Malta. There are a number of intriguing socio-political reasons for the troubled evolution of modern art locally. In the following discussion, Maltese Art Historian Nikki Petroni shares some insights on this dilemma, as well as other interesting thoughts concerning Malta’s modern and contemporary art scene.

EVE COCKS [EC]: Last year I attended a lecture of yours, entitled ‘Modernity, Tradition and Perception of Art in 20th Century Malta’. This lecture, correct me if I’m wrong, formed part of your current PHD research on the dialectics of tradition and modernity in Maltese twentieth-century art.

NIKKI PETRONI [NP]: That’s right. It was a pleasure to see you there, as always.

EC: It is generally held that modern art in Malta did not flourish, or developed rather late, however many of us do not know why. During the talk you’ve mentioned that the Church was one of the various factors that contributed to such a delay.

NP: The church had dominated the way people thought more than politics did, in fact religion was something that really contained an idealised notion of Maltese identity. With the presence of a protestant colonial power, being Roman Catholic was one way of not being the coloniser, and I think that played a big factor in shaping people’s beliefs and self-awareness. In fact, I am quite sure that the traditional aspect of Maltese identity was actually reinforced in the modern period because it became something that was a form of resistance to the new and foreign. There were other factors that restrained the development of modern art such as people’s limited access to knowledge, which is something that the church and the government tried their best to control.

EC: So the Church didn’t accept the modern aesthetic because it was not suitable to inspire or teach people its doctrine?

NP: The Church did not accept modernism as a way of life in general, not just as an aesthetic practice. Capitalism, individualism and women’s rights, for example, were all values that the Church was vehemently against, and by Church I am referring to the Vatican as well as the local diocese. However, it is very important to keep mind that one cannot completely blame the Church for the slow development of a modern language for Maltese art as there are many other factors to consider. The rise of Italian nationalism greatly influenced artistic alliances and aesthetic choices. I also would like to point out that slow or delayed developments are associated with peripheral countries and spatial territories. Places that are not central metropolitan areas of the Western world are considered backwards. We consider France as being more ‘advanced’ or ‘avant-garde’ because Paris was the birth place of modernism. However, France also has its provincial areas that were not up-to-date with Paris. Provinciality is an issue that every country deals with, whether it’s the US, UK, France or Germany. And when you realise this, you will start to reposition Malta within this whole landscape of artistic and cultural development. I will be going into more detail about this in my thesis.

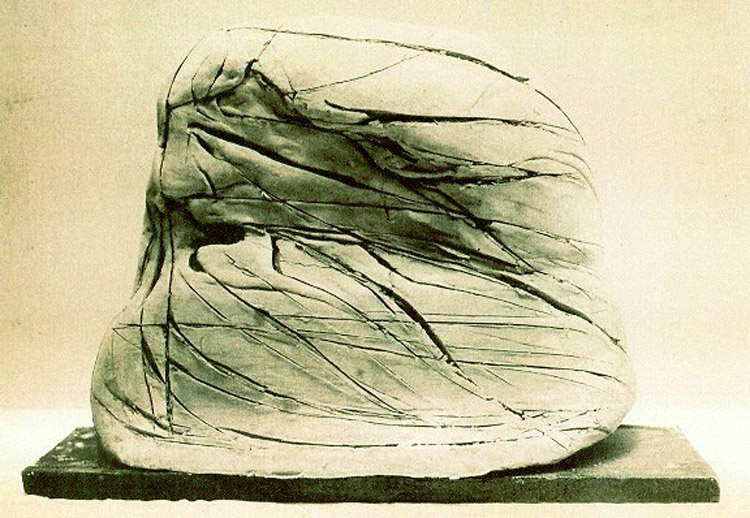

Enigma by Josef Kalleya

Photo Credit: Nikki Petroni

EC: Therefore, you don’t consider Malta as having remained backwards?

NP: Well, if one compares art in Malta to contemporary currents in Paris or Berlin, the immediate reaction would be to realise that Malta did not have an avant-garde culture, and it’s true, we didn’t have an avant-garde or any radical revolutions or statements against the state and the church. Manwel Dimech fought for radical social values, he tried to push for complete independence and social justice in the 1910s. For his efforts, Dimech was exiled and excommunicated. I think that many were scared of such repercussions. But, what I’m really trying to posit is that, there are many politic levels that determine slow or restrained cultural development.

EC: During the talk you’ve also mentioned that there was a particular ‘tension’ between Maltese modern artists and the Church.

NP: The tension was in the fact that many artists did not confront the church or challenge its criteria of art production, or even society’s norms in general. Maltese artists were reluctant to disrupt society’s complacent state. Artists suppressed the cultivation of modern art themselves by largely complying with the establishment and purposely concealing non-conventional artworks.

EC: Although Malta’s modern art scene was delayed due to several different factors, you’ve tried challenging ‘Malta’s backwardness’ by focusing on a few examples. You’ve discussed artists such Antonio Sciortino, Robert Caruana Dingli, Josef Kalleya, and Emvin Cremona, right?

NP: Yes, those are the ones that I mainly focused on.

Left: Broken Glass by Emvin Cremona

Right: Broken Glass by Emvin Cremona

Photo Credit: Nikki Petroni

EC: Can you kindly explain why you’ve chosen, let’s say… Robert Caruana Dingli or Emvin Cremona as examples?

NP: I focused on Robert Caruana Dingli because in 2016 ‘Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti’ published a book on his private letters, and in these letters Robert heavily criticises his brother Edward Caruana Dingli as well as Giuseppe Calì and Gianni Vella. In a nutshell, all those artists whom he thought were sell outs, who used to imitate and copy rather than create. Edward, for example, used to copy people’s portraits from photographs, whereas Calì and Vella used to imitate the stylistic schema of local church art, only introducing subtle changes. These repetitive works sustained the hierarchical function of sacred images. This bothered Robert. For him, these types of artists painted what the people wanted, what the kapillan and popolin were pleased to see. He believed that such art was void of authenticity and a lacked direct relationship with nature. These letters are very striking, because I never encountered the writings of another Maltese artist who criticised other artists and the Maltese public on aesthetic terms prior to the years in which they were written; around and immediately after the first world war.

On the other hand, I spoke about Cremona because that which he was producing in Malta and what he mainly exhibited in London was not synchronous. In post-WW2 Malta, Cremona was painting figurative altarpieces in Churches, receiving auspicious commissions. Yet he was concurrently painting abstracts, which speak a completely different language. In the mid 1940s Cremona lived in London and he was well-acquainted with the art scene there.

EC: If I had to ask you when did the first signs of modern art in Malta appear, what would you say?

NP: This is something which I had tried to explore at the beginning of my research but I eventually realised that it was more important to work towards a definition of what the modern is in the local context and to study the diverse nuances of ‘modern’ as a temporal concept. Nonetheless, I actually think that the first artist who entered into modern subjects and aesthetics was Antonio Sciortino. In 1904 he had produced his Les Gavroches, which makes explicit reference to Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, dealing with the revolutionary children of Paris. This is one of the earliest, if not the earliest pieces, of modern art in Malta.

EC: And when do you think Modern art flourished?

NP: Definitely after the Second World War, 1950s on, when there was a group of young artists trying to find a new language, trying to seek something new.

My Life by Frank Portelli

Photo Credit:https://www.facebook.com/FrankPortelliArtist/

EC: This group of artists included Emvin Cremona, Frank Portelli…

NP: Yes, as well as Josef Kalleya, Antoine Camilleri and Carmelo Mangion, although Kalleya and Mangion had already been working in a modern idiom in the first half of the century.

EC: Stylistically, did these artists share any common elements?

NP: Maltese modern artists developed their own modern languages and were influenced by a diversity of sources. However, there were common elements. Most of them questioned Maltese identity and history, faith (which was one of the biggest challenges at the time) as well as the influence of western modern art; particularly the works of artists such as Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky and Jackson Pollock. They were aware of modern developments and attempted to understand it and integrate their ideas into their art.

EC: I mean…even today modern art is difficult to come to terms with, let alone back then when it was still at its peak.

NP: Of course.

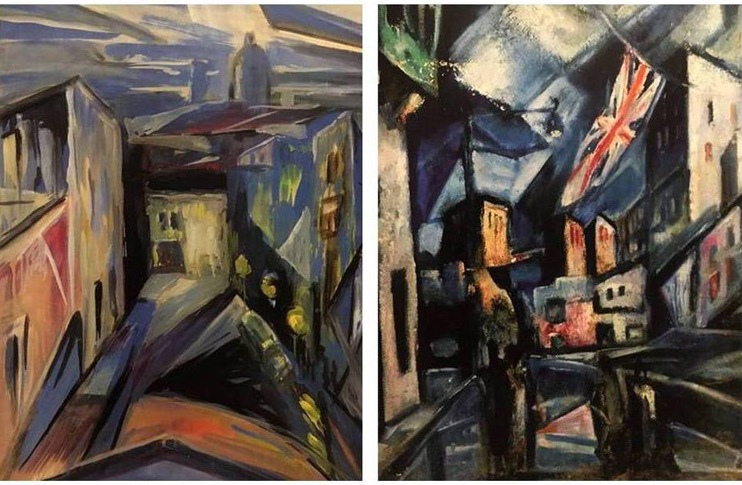

Left: Street Scene with Cars by Carmelo Mangion

Right: British Malta II by Carmelo Mangion

Photo Credit: Joseph P. Cassar (Carmelo Mangion: His Life & Works)

EC Do you think the Church still has a say in today’s art scene?

NP: Not really. Today, the state art and cultural institutions are establishing criteria and parameters for art production. The art establishment is the state.

EC: Could you elaborate?

NP: Institutions impose what kind of subjects artists must address by releasing open calls and drawing up cultural strategies and guidelines. I am very critical of how some institutions and funding bodies work, I mean, don’t get me wrong, I want these opportunities to be there and they must be offered, but we have to be clever about how to use them.

EC: What do you think about Malta’s contemporary art Scene? Is it growing or improving?

NP: It is definitely growing, but I’m not sure about improving. I know I’m being a bit cynical but only a few artists are producing very exciting work. The problem is that, a lot of art students are detached from their history. There are many who don’t even have knowledge of Western art history, and that’s troubling because you have to know what came before you in order to be innovative. Everyone today seems like they want to do things without knowing what came before them, they do not engage with modern and contemporary art history.

EC: Is there anything else that you would like to add? Maybe a word of recommendation to young upcoming artists – a tip on what they should do to reach international standards.

NP: Leave your home when you are seventeen, don’t get any more food from your ‘nanna’, pack a bag and leave the country! What I mean to say is that: to create art, artists need to work together, form collectives, and share ideas. This is what will make them and their art dynamic and innovative.

Nikki Petroni read for a BA in Art History at the University of Malta and was awarded an MA in the same subject from University College London (UCL). She is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Malta researching Maltese modern and contemporary art. She has curated various exhibitions and has edited a number of academic publications. Nikki is an arts and culture columnist for the Malta Independent on Sunday and editor of Patron Magazine.

FEATURED IMAGE: Courtesy of Katelia Art https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100012271183576